With your left foreleg, “The Marseillaise” with your rightįoreleg, and “Where Have You Gone, My Last Rose of Simultaneously beat time to the tune of “The Volga Boatman” You must all count backward from a hundred and ten toįive as quickly as possible while thinking of your own fateĪnd weeping for those who have gone before you.

In the intensely cold room in which several other horse attendees are gathered, Lady Fear speaks of a new game she has created to entertain her dining friends. the horse picks her up to attend the party at the Castle of Fear, fear herself being the mistress of the house. The seemingly friendless protagonist is glad to have the horse as a friend, and accepts his offer.

Soon after, the horse admits that he is bored with his job as tour guide, and that the floor is not quite as beautiful as he has described it he then further invites the woman to another party that same evening.

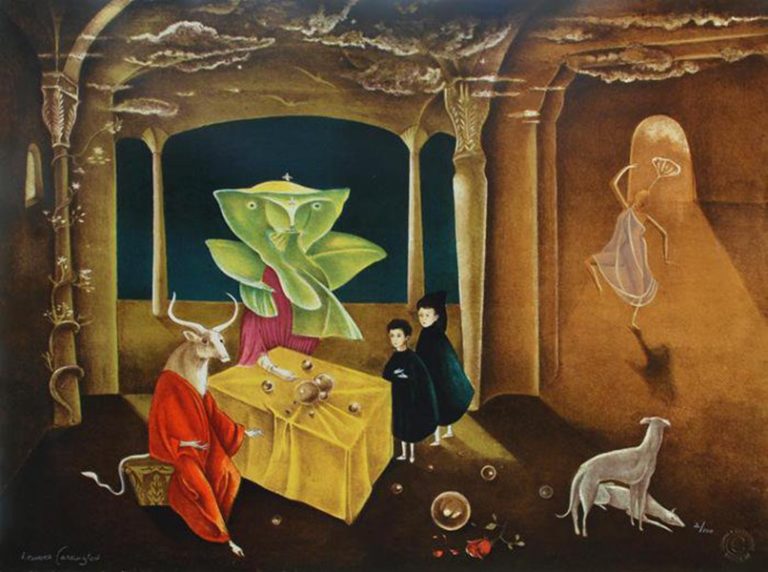

In “The House of Fear,” from 1937-1938, for example, while “walking in a certain neighborhood,” the central figure is suddenly stopped by a horse who demands she come with him to a strange house, filled with creatures in ecclesiastical dress, to see the “beautiful inlaid floor” made of turquoise, stuck together with gold. With their half-forgotten narratives, their ragged and inconclusive endings, and a focus on visual images as opposed to plot, one might describe Carrington’s writings as being scenarios or literary tableaus which gather her characters into a single space before abruptly ending. But Carrington’s writings do not accord with the standard tales by the Grimm Brothers, Hans Christian Andersen, Peter Christian Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, or even the short prose romances of Charles Perreault and other French authors. Despite the title of this beautiful book, The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington, the author’s writings are not what most readers would define as traditional “stories.” In some way the works are similar to fairy tales, most focusing on speaking animals and magical creatures.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)